Building Stanford's "Generative Agents" with TypeScript and Rust

Contents

Everyone's had the idea to make a village of LLM-powered NPCs, but how many people have actually built it? This article documents my journey; where, for a fleeting, blissful moment, I had the coolest job in the world.

Part I: background🔗

Back in the halcyon days of 2023, when I was working at Employer Who Shall Remain Nameless (hereafter EWSHARN), ambitions were flying high. Our product was a distributed computing system, and we needed to demonstrate use cases. We'd built the usual quotidian proofs of concept: chat app, card game, etc. Yet, EWSHARN was abuzz with talk of a moonshot SO outrageous, it was more likely to hit Mars than our own dear Luna. The project was called EW-VILLE (names have been changed to protect the innocent).

The plan? Build Stanford's Village, but multiplayer. How hard could it be?

Spoilers: very hard.

Look! Short form video content!🔗

Most of you will have left this page by now, so to keep you interested, here's a video of the game in action!

This isn't a video of the experiment itself - that took over an hour to run - but you can see the little player eavesdropping on an NPC conversation, and implanting an idea in Lobelia's mind about Goobert.

Part II: how it worked🔗

const prompt: LLMMessage[] = [

{

role: 'user',

content:

`You are ${npc.name}.

About you: ${writtenIdentity(npc)}

You just saw ${humanReadableList(audienceNames)} and have begun a conversation.

You last spoke with ${audienceNames} ${lastConvo?.started ? moment(lastConvo.started).from(timeToMoment(npc.server)) : 'a while ago'}.

${npc.taskDescription ? `Just now, you were doing this: ${npc.taskDescription}` : ''}

${audience.map(a => npc.conversationWhitelist[a.guid] ? `You have planned to speak with ${a.name} about ${npc.conversationWhitelist[a.guid]}

` : '').join('\n')}

Please greet them.

${audience.filter((r) => npc.relationships[r.guid || r.name])

.map((r) => `Relationship with ${r.name}: ${npc.relationships[r.guid || r.name]}`)

.join('\n')}

${topMems?.length ? `Relevant memories to this conversation:

${topMems.map(m => `- ${m.description}`).join('\n')}` : ''}

${npc.name}:`

An example of a formatted prompt for an NPC.

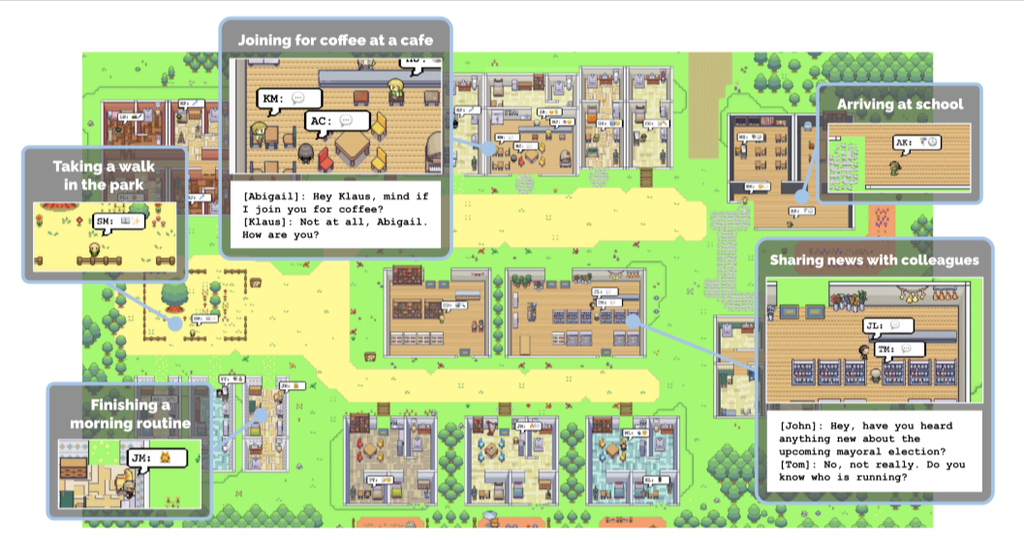

World -> Perceptions -> Thoughts -> Actions🔗

The basic idea is that your NPC is in a world composed of other creatures, items, and locations. When they're taking a turn - which they do every tick of time - they observe the things within their sight radius and receive descriptions of the state of those things. These create perceptions which, every few turns, the LLM will process in batches to create moment-to-moment impressions that the NPC is thinking at a given time. "I notice that Jane is sipping coffee while feeling sad." "I notice that there is a tomato on the counter with a knife sticking out of it and a sticky note attached." "There is a large group of people laughing together in the library." That sort of thing.

Enough of these impressions combine to form thoughts, and thoughts optionally produce actions on the part of the agents. "I will go walk over there and speak with so-and-so." "I will take the knife out of the tomato, read the note, and proceed to chop it." "I will create a trinket to bring to such-and-such because it will make them happy."

// How world objects become perceptions:

const englishDescription = (perceived: Perceivable, location: Location) => {

if (perceived instanceof Item) {

return perceived.getDescription() + ` in ${getFullPath(location)}`

} else if (perceived instanceof ServerNpc) {

return `${perceived.name}${perceived.taskDescription

? `, doing the task: "${perceived.taskDescription}"`

: ''}${perceived.asleep ? ', sleeping' : ''}`

} else if (isNote(perceived)) {

return `a note: "${perceived.content}", posted by ${perceived.author}`

}

}

In this version of the game, the thoughts that they have are action-oriented. When they have a thought, it usually produces an action on their part: they're going to create an item, walk to a location, or talk to somebody. Then, provided that they need to change their location in order to perform the action (walk, talk, or "go to the library"), they'll be occupied doing that until they accomplish the task.

Notable exception to this: if they've decided to talk to somebody. We have an internal whitelist of names that the agents have elected to have conversations with. If I plan to talk to Jody, then the next time I see Jody - even if I'm in the middle of doing something else - I'm going to be able to go up and start a conversation.

This creates the interesting result of possibly having an agent stuck attempting to do a task all day long while they keep getting interrupted. The simulation is not yet sophisticated enough to actually make them experience annoyance at being unable to complete their tasks, but the building blocks are there.

On the game dev/simulation side of things, I architected a deterministic operation pattern for multiplayer synchronization. In this case, it wasn't multi-human player, but multi-agent player, because you can kind of think of them as players. The player themselves - the human player, that is - is also sending actions to this queue (although some player actions perform instantaneous mutations to the game state, most of the game-like actions that they can do are simply pushing to the operation queue). And writing the game loop, the god function that chugs through all of the pending operations and performs them one by one, was a lot of fun. Even though I know that god functions are not necessarily the best thing to have in especially large distributed systems - I foresee having to refactor this into a different sort of system, probably ECS, if we ever take it to the next level of having actual multiplayer - but for what it was, it was a very robust component of the game logic, which kept us afloat when everything else seemed to be burning around us.

Confabulations: "What do you mean I can't bite the leg off of the table?"🔗

A screenshot of Stanford's NPC village.

One of the first issues we noticed with this system was that the agents would often confabulate properties of the simulation: assuming the ability to use arbitrary items for arbitrary tasks, then becoming frustrated attempting the same action in multiple different ways, or assuming that an action is completed when in fact they've done nothing.

Example: I'm going to jump onto the table and start dancing. When you're collapsing an intent like that into simply moving next to the table, the other NPCs in the simulation are not going to witness them dancing - unless you have some kind of status line that the agent can set on itself to say that they are dancing on the table. We did eventually end up creating something like this, but at first it wasn't there.

Another more egregious example: I'm going to go to the kitchen and start baking some bread. We didn't have the ability to create items, so the NPC walked into the kitchen and promptly forgot about anything they were doing in there, because their action had no effect on the world other than to simply reposition them.

The converse of this, however: once we enabled NPCs to create items with their intents, they were starting to do this all over the place multiple times a day, and your kitchen is now full of immortal, imperishable apple pies and breads and cookies. The NPC doesn't really seem to be reacting to the fact that they've got a list of 12 different baked goods in the kitchen in advance of the party. They're going to keep doing it because they're in a kitchen full of delights. Ah, what a blissfully cozy kitchen this is! A few more desserts are just what the doctor ordered. [Create 10x breadsticks]

So how did we solve the repetitive items problem? We eventually began to append recently completed actions and pending goals to the prompts we send them when asking what they want to do. We ended up creating a "running commmentary" of recent goals and actions to help keep them on track with these obviously pseudorandom moment-to-moment whims to create some semblance of willpower and coherence.

Speaking for others: "And then, we kissed."🔗

Another thorny issue we ran into was when the agents would decide to fill in the other's dialogue for the next turn of the conversation. Alice and Bob are speaking to one another, and Bob generates his line of dialogue. Hello Alice, how are you? But Bob keeps going, and he spits out, Alice, colon, I'm fine, how are you, Bob? I was just thinking about you this morning. Maybe a little wish fulfillment on the side of Bob, who knows? But we can't have people talking out of turn in conversations, or filling in the responses for other agents, because they're not being prompted with the same internal thoughts and memories. They don't know everything the other agent knows. And this is actually becoming a believably agentic problem here, where if you try to have somebody talk as somebody else, they're not going to do a very good job of it, unless they know them very, very well. And even then, there are secret memories that we all have, right? Stop words, which are a feature of the API, which I also had to eventually implement above the API, because not every agent API supports it at the time, came to the rescue. Because we can simply chop the utterance at the first occurrence of interlocutor's name plus colon, in order to obtain something that we can be reasonably sure is a line of dialogue. Now obviously, it's not foolproof. But when you're running hundreds of conversations a minute, then you don't need it to be foolproof. You just need it to be 95, 98, however many percent. You don't care so much about false positives, as you do about false negatives.

function stopWords(me: string, them: string[]): string[] {

return them.flatMap((stop) => ['\n' + stop + ':', '\n' + stop + ' said:'])

}

Medium- and long-term memory🔗

Stanford's "generative agent architecture", the memory model that makes it all tick.

Long-term thoughts are another important component of the system. Moment-to-moment thoughts, of course, are what inform the context around the actions that an agent will elect to perform. But every couple of hours, the agents also coalesce their logs of momentary actions, observations, and thoughts into long-term goals, beliefs, and emotions.

Additionally, when the agents reflect upon recent and past events, they create citations in their mind of the memories which elicited those reflections and conclusions. So you can create memory chains going back in time of, you know, I saw a green roof, I thought it looked nice, I picked a green dress to match the green roof, my crush complimented my green dress, there's a causality there which is established by the citation of past memories. The experiment did not directly check the efficacy of this particular structure, however, it was present, it was functioning, and so I think to remove it would be another way of checking whether the juice is worth the squeeze. I suspect it is. This functionality is also mentioned directly in Stanford's paper.

interface Memory {

id?: number

npcId: string

importance?: number

lastAccess: string

createdAt: string

type: 'perception' | 'experience' | 'reflection'

relatedMemoryIds: number[] // citations!

description: string

}

In the experiment we ran, one of the salient examples of this was when we decided to try and set up two of the agents in a relationship with each other by giving one of them a crush. They repeatedly expressed emotional attachment to their would-be significant other when they were talking with them, and they began to feel emotions when they were separated from them. The object of the affection also quickly caught on to the state of affairs. They would look for each other and get nervous and flirtatious when they were able to speak together. This was very interesting because there were these running emotions influencing their moment-to-moment actions.

Although it was not the main intent of the experiment to see whether these behaviors would be elicited - the main intent was to see whether most of the people invited to the party would actually go to the party - it was still one of the more touching phenomena to witness, in a way.

Embeddings in a vector db (Pinecone)🔗

Of course, accessing dozens and hundreds and thousands of memories can get very expensive very quickly. Additionally, we often want to trigger similarity searches for memories if, for example, you saw a dog bite your friend, you really want to remember that conversation you had the other day where you noticed that there were bite marks on their hand to be able to make a connection - and you might not think, as an LLM agent, to search for the word bite in your recent memories. And anyway, we might not even be prompting you to do an explicit word matching search across your entire memory database because that would get really expensive really fast. So we had a vector database, which was Pinecone, to do similarity search on phenomena for certain kinds of memories in order to make associations and provide them to the agents for when they form these higher-level experiences and reflections. This way, if they saw someone sipping a cup of cocoa multiple times, they would be able to see in their memory that they had had memories before of them drinking cocoa, and they may be able to draw a conclusion that, wow, this guy really like cocoa, as this becomes notable with increased frequency.

Of course, we cache embeddings using SQLite to avoid recomputing them to save API costs and latency.

const queryVectors = async (tableName: string, text: string, filter: object, limit: number) => {

const pinecone = await pineconeIndex()

const { embeddings } = await fetchEmbeddingBatch([text], fetch)

const { matches } = await pinecone.query({

queryRequest: { topK: limit, vector: embeddings[0], filter },

})

return matches.map(({ id, score }) => ({ _id: id, score }))

}

Durable actions🔗

Another very useful and later essential component of the system was the upgraded actions system. In this system, we not only allowed the NPCs to create instantaneous actions, such as create an apple on the table, or destroy the apple and create a sliced apple, or walk to the library, or initiate a conversation with Bartholomew, we also allowed them to attach an expected duration to the action that they intend to take. So if I'm the blacksmith, I can forge a sword, and I predict, as the blacksmith, that this is going to take me about 6 hours. Now, your insensate author does not know exactly how long it takes to forge an entire sword, but the agent can make a good guess, and at this point in the project, good guesses are all that we need. This also created some hilarious circumstances where, for example, the sentient ball of slime, Goobert, R.I.P., would choose to mope that nobody understood him as an activity for 6 hours, or isolating himself in his chambers and meditating on the works of William Shakespeare, or similar such things, essentially taking himself out of the social interactions for the entire duration of the simulated day.

interface DoTaskInteraction {

type: 'doTask'

description: string // "forging a sword for the baron"

duration: number // minutes

affectedItems?: UpdatedItem[]

}

Part III: the experiment🔗

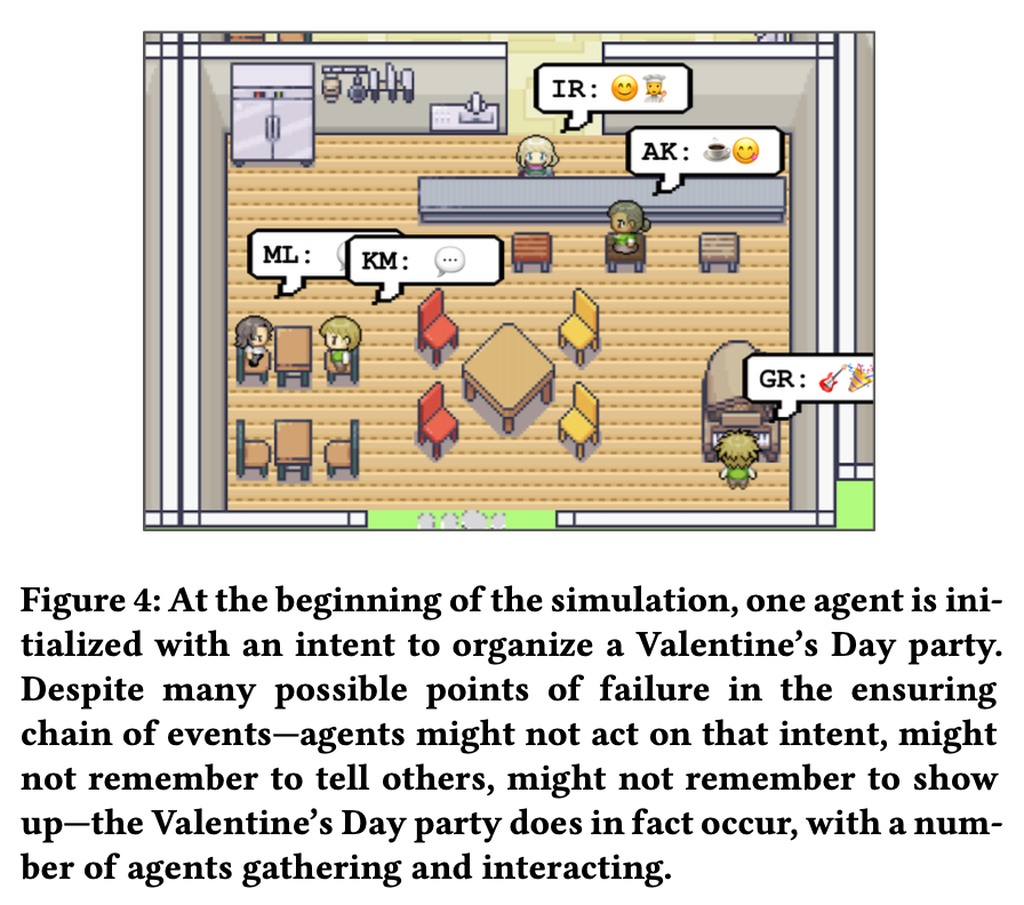

Stanford's Valentine's Day screenshot.

So, how did the experiment actually shake out? By now, I've crowed enough about the fact that it was a success, but I should note here for those of you who've been good enough to read this far: it was not an unqualified one.

The method🔗

The player (your insipid author) approaches an NPC at the start of the simulation and suggests to them that they should throw a Valentine's Day party to kickstart the love lives of the other younger NPCs in the village. From that point on, the method is simply to sit back and watch. Although there were some runs of testing where steering the NPCs towards certain actions was necessary to assess the effects of certain kinds of thoughts on the agent cluster as a whole, there was no additional steering allowed for the actual experiments beyond the initial idea inception.

So: the NPC (I believe it was Grandma Lobelia) goes and begins inviting people to her "arranged marriage" party. Being something of a busybody, she's going around the town and having conversations with everyone she can, telling them about this party that she's going to be throwing and insinuating the need for more connections between the villagers. Many of the agents were very happy to be invited - in fact, I don't think anybody rejected the invitation except for maybe the living ball of slime who's very depressed but also a fan of Shakespeare.

In the background, of course, the other NPCs are trying to find each other to talk to, trying to create art, studying in their laboratory, forging at the blacksmith's, and that sort of thing. But that's not the focus of the experiment.

The results🔗

There were a few in-game days which elapsed before the party proper (which is part of why it took so long to run at one game-minute per second of real time), but once the day arrived, almost everyone in town was aware that the party was happening. Many of them arrived at the location early - and I mean really early. We're talking 8 AM for a 6 PM party.

But it was a bit funny, because there seemed to be a disconnect between what the user was seeing and what the agents were thinking was happening. They would start walking to their house, and by the time they got home, the entire morning had passed away - or more extremely, it was now mid-afternoon because they happened to have a real-time conversation with a different NPC that went on for a lot of turns. One possible approach to mitigating this phenomenon of waylaying an NPC for an entire day (at the end of which they are required to sleep, more or less - some night owls would just keep working, but only because they had queued an hours-long action) is to limit the number of turns a conversation can take.

Even with that handicap, however, 80% of the NPCs made it to the party on the day of the party. Not a lot of them actually got there at the 6 PM timestamp, but I believe that's due to the asynchronous nature of their actions with relation to the time in the world. There was Grandma Lobelia in the party venue preparing it constantly the whole day long. (This was a durable action with, sadly, no external artifacts - she just stood there and "prepared". Something to look into for future implementations.) Several showed up and thought the party was going when it wasn't. But the fact that they were there and celebrating, even though it wasn't the actual universal time of the party's beginning - I think it's something of a positive note.

Post ferias🔗

And even after the party officially ended, they continued to trickle in and have conversations with one another about the party and their friendships and many such things. It was also very sweet seeing the Romeo and Juliet figures start crossing each other across town as they went looking and missing each other. And Goobert the slime seeking companionship, alien though he may be to the other human beings of the village.

Durable events🔗

Although it was not a component of the experiment itself, after the experiment, this desynchronization phenomenon inspired us to reify the concept of events in the game as a universally accessible and invitable entity at the level of the simulation. So, in future iterations, Grandma Lobelia would be creating events and inviting other agents to them, and then, in the prompts which agents receive when they wake up to plan their day, they would be reminded that these events are going to occur later on.

The full ramifications of the events system were not fully explored by the time the project got cancelled, but you can easily imagine things like double dates, study sessions, and even more expansive contexts like battles and barn raisings, could all be organized via this system with much greater fidelity in regards to who shows up when and what tasks they're able to accomplish together. Stanford didn't do this, but I believe that some kind of universally accessible store of planned events - you might even call it a calendar (which I believe is the vernacular term for such a database) - would be extremely interesting to investigate the ramifications of.

interface ScheduleEventInteraction {

type: 'schedule'

name: string // "Valentine's Day Party"

description: string // "a party to celebrate love"

location: string // "Bethlehem Bar & Grill"

start: EventTime

end: EventTime

}

Finis coronat opus🔗

That's the broad level overview of how it went. Obviously there are lots of things to improve upon, but the long-term memory, mid-term memory, and short-term observation, along with item creation and conversation whitelist, were essential to making it all jive, and shouldn't be set aside for anyone building out a similar system in the future. Item destruction I didn't really ever see used, although if someone were eating a piece of bread I could see it coming out a lot more often. I'm not sure I would want to program in a hunger mechanic though. That sounds like a nightmare. As for romance - who wants to put rules to that? Still, a codified relationship graph would probably confer similar benefits as a calendar.

A glass, darkly🔗

And despite all of this, at the most sophisticated incarnation of the simulation, we still ended up with confabulations about the world model that the LLMs would attempt to engage with. "I will dig a hole under the ground and tunnel up into Briselda's house." There's no mechanic for doing that, but the LLM believes it's in a completely verisimilitudinous one-to-one simulation of the world, and so of course it's going to try things like "I'm going to chuck a poker chip at her head to get her attention." There's no throwing mechanic! I'm not going to program a throwing mechanic into my simulation. But at some point you do kind of want a general action or something to encompass the broad categories of thing that an agent might try to do.

You might have a poker chip throw classed under "attack"; you might have a dodge classed under "defend"; but then, you have to get into what your model of combat is. It's very thorny territory, in which you eventually end up attempting to pixelize the fractal, continuous, indefinable space of all possible actions into a discrete set of maneuvers - which is not very much different from the way you have to write rules for a tabletop role-playing game, or even a video game. But I digress.

// The discrete set of maneuvers we ended up with:

type WorldInteraction =

| WalkToInteraction

| TalkToInteraction

| DoTaskInteraction

| SleepInteraction

| PostNoteInteraction

| ScheduleEventInteraction

| ContinueTaskInteraction

Part IV: why you can't play this right now🔗

Well, there's a sad end to the story, and this is the part where it becomes a nightmare.

I had written the back end in TypeScript. I had written the front end in TypeScript. I used Phaser.js, the game library - which, speaking of shoutouts, I need to give another one here to Richard Davey, who makes Phaser. Especially because he met with me on a video call and helped me hash some things out before I lost hope and abandoned the project, and myself, to go walk out into the mountains and raise goats for the rest of my days. So: use Phaser when you're making games. I've done it twice. It's very nice, and it suffice [sic].

But why did the project turn into a nightmare?

Well, as I was saying: in the golden age, it was TypeScript, up and down, all the way around, and I knew it like the back of my hand. And then it turned out that async/await were not available in Wasm, which it was necessary to compile all of the server-side code to, in order for it to run on our product's decentralized compute nodes. So I couldn't actually wait for the stack of 12 different things to happen (perceiving, interpreting, memorizing, conversing, etc.) when the LLMs were streaming these server-side events. We had to completely change the model on the back end in order to work with the Erlang-style inter-process message passing that our platform had decided to implement at the base level.

So, that's problem one. Problem one and a half: we were on a deadline.

Problem two: it was Rust.

Rust the plan🔗

At the time of the refactor, LLMs were much worse at code gen, and I hadn't written a line of Rust in my life. (You can maybe start to see how the problem is beginning to take shape.)

Thankfully, it wasn't just me working on the project. My partner in crime, Billy, was also working on it with me. While I was frittering away the hours putting tiles in a level editor, he was in the trenches reading my TypeScript code (which I would not wish on anyone) and turning it into the equivalent - or something like it - Rust code (which I also would not wish on anyone, but I would even more not wish it on anyone than I would the former).

He got pulled into a different thing, though; and so, after the project was in a state somewhat resembling working, I was solo on both sides of it again. The task at hand was feature parity with the TypeScript version. It's sad to say we didn't get there. There were so many unknown delays with getting the text into the right places at the right times, passing it over our network, and reassembling it on the front end, that behaviors we had come to know and love - like the charming ability of the NPCs to have conversations - were just... gone. Pending response flags got mismatched, architecture metamorphosed, and the system just wasn't tied together right.

I'm not necessarily using this as an opportunity to rag on Rust. Two senior developers who are Rust juniors, encountering it for the first time, trying to translate an existing code base on a deadline for an experimental R&D project, working with tons of asynchronous and synchronous calls, who need low latency, and managing emergent effects over long periods of time to obtain diaphanous LLM-centric phenomena... is a bit of a tall ask for anyone of any background.

But since it was such a tall ask, we spent a lot of time on it. And when it wasn't happening quick enough, the project got canned.

And that's the story of how I almost made a billion dollars creating multiplayer NPC villages for you to fight with one another, farm for resources, and pay cryptocurrency to speed up time or something like that. The exact implementation of how billionaire status would be acquired was never quite nailed down. But if I were crazy, I might try to make something like that again. And maybe that time I would succeed.

Part V: code reflections🔗

How was it in terms of code? Well, I've had worse. The asynchronous server-side event streaming was a bit of a nightmare to try to marry to a game world that was progressing through time at a constant pace. You really want to be able to take turns with an LLM in a more step-by-step fashion. But the conceit of always-on multiplayer NPC village demands a constant progression of time, especially if you want to keep things fair between other players who may eventually be going to war with one another with these agent factions.

At the end of the project, I think we did have something remotely resembling fairness, where the slowness or quickness of the actions of your NPCs was more or less determined by how responsive the servers were. But it's conceivable that you might be able to use a fast model, that didn't necessarily have to do deep thinking, in order to gain advantage over your peers. Whether or not we wanted to lock other people to the same model as everybody else is an exercise that we unfortunately did not get to do, because we never got to financialization. Oh well.

Quantus tremor est futurus🔗

So, was the project a failure? Was the project a success? It depends on what you mean. I made the game work, and it didn't translate to the format it was needed in, but if I wanted to pick it up again and keep going, the game is right there waiting to be developed, and all it takes is a sufficiently loony individual to bring it to full maturity.

Acknowledgments🔗

I'd like to thank from the bottom of my heart Kenney, the game dev whose all-in-one assets resource was extremely useful. It was essential to the building, testing, and completion of this project. I can't thank you enough for what you've done for me, or the game dev community at large.